40 Mile Desert

Churchill County

The 40 Mile Desert was a long, desolate stretch of the Carson Trail north of Fallon. At the large natural dike separating the Humboldt Sink from the Carson Sink, the California Emigrant Trail forked into two

different routes. The earlier Truckee Route (1844) followed a path towards the Truckee River near modern day Wadsworth, while the later Carson Route (1848) turned to the

south, crossing the infamous desert before arriving at Ragtown and the Carson River. Water was scarce, and that which could be found was unusable (see Humboldt Double Wells and Salt

Creek Crossing below, as well as Soda Lake). Usage of the Carson Trail grew after 1849, when it became the primary route to California. An 1850 survey of the dreaded desert crossing

gave this grim statistic: 1,061 mules, 5,000 horses, 3,750 cattle, and 953 emigrant graves were strewn across the forty mile stretch. After 1859, with the inception of the Central Overland Route, emigrant

traffic across the 40 Mile Desert declined, and all but ended with the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad a decade later.

The map below shows the Carson Route and landmarks across the 40 Mile Desert. Nearly a dozen markers placed by Emigrant Trails West, Inc.🔗 are also shown.

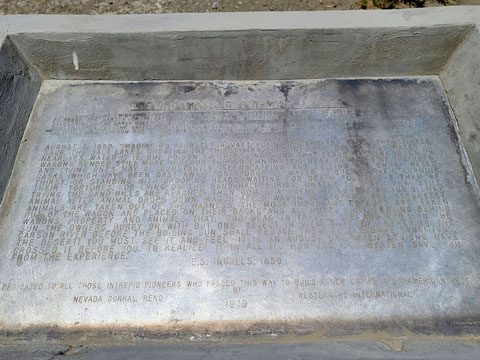

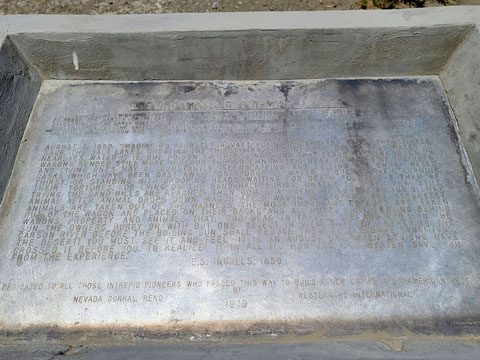

A large concrete marker and plaque placed in 1979 stand alone near the mid-point of the trail. The difficult-to-read plaque is inscribed as follows:

The Infamous Forty-Mile Desert

California-bound emigrants were forced to cross this desert devoid of forage and potable water in order to reach the Carson or Truckee Rivers. The loss of property, wagons, livestock, and human lives was

staggering in the early Gold Rush years. Sometimes called the Valley of the Shadow of Death, this desert was compared to Dante's Inferno. The following is from one of those pioneers who wrote this moving

account in his journal:

August 5, 1850: "Imagine to yourself a vast plain of sand and clay…the stinted sage, the salt lakes, cheating the thirsty traveler into the belief that water is near. Yes, water it is, but

poison to the living thing that stops to drink. Burning wagons render still more hideous the solemn march; dead horses line the road, and living ones may be constantly seen lapping and rolling the empty

water casks (which have been cast away) for a drop of water to quench their burning thirst, or standing with drooping heads, waiting for Death to relieve them of their tortures, or lying on the sand half

buried, unable to rise, yet still trying. The sand hills are reached; then comes a scene of confusion and dismay. Animal after animal drops down. Wagon after wagon is stopped. The strongest animals are taken

out of the harness; the most important effects are taken out of the wagon and placed on their backs and all hurry away, leaving behind wagons, property, and animals that, too weak to travel, lie and broil in

the sun…The owners hurry on with but one object in view, that of reaching the Carson River before the boiling sun shall reduce them to the same condition…The desert! You must see it and feel it in an August

day, when legions have crossed it before you, to realize it in all its horrors. But Heaven save you from the experience." - E.S. Ingalls, 1850

Dedicated to all those intrepid pioneers who passed this way to build a new empire in our American west.

by Nevada Corral, Reno & Westerners International, 1979

Humboldt Double Wells - Also known as Emigrant Double Wells, this was the location of two wells dug in an attempt to obtain potable water. After discovering the first well was bad, a

second was dug just a few feet away; it too turned out to be bad.

Salt Creek Crossing - Moving south, the emigrants reached the Humboldt Slough or 'Salt Creek'. Out of necessity, stones and boards were used to fashion a crude crossing for the

wagons.

Near Soda Lake and the southern end of the desert, another great interpretive plaque erected by the Oregon-California Trails Association could be found. It disappeared around 2013.